Overview of the Chhé’ee Fókaa People (a.k.a. Salt Pomo or Northeastern Pomo)

The Chhé’ee Fókaa (čʰéʔe: fóka:) Pomo people of the Stonyford area in Northern California are the only Pomoan group native to the Sacramento River drainage (McLendon and Oswalt 1978: 285-286). Their ancestral language is one of seven Pomoan languages, and linguistic analysis supports their having been in their current homeland before the arrival of Wintuan speakers (Nomlaki and Patwin languages); as such they are a “relictual” Pomoan community (Walker 2016: 88-89).

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Chhé’ee Fókaa controlled a valuable salt deposit just outside of the modern town of Stonyford, hence their self designation as Chhé’ee ‘salt’ Fókaa ‘people’. The Spanish and Mexican period saw the murder and enslavement of the Chhé’ee Fókaa people (Kroeber notebook 204, Pitkin Papers). So few survivors remained that American academics had no knowledge of the existence of Pomoan peoples in the Sacramento Drainage until they were identified by Samuel Barrett in the first decade of the twentieth century (Barrett 1904, 1908).

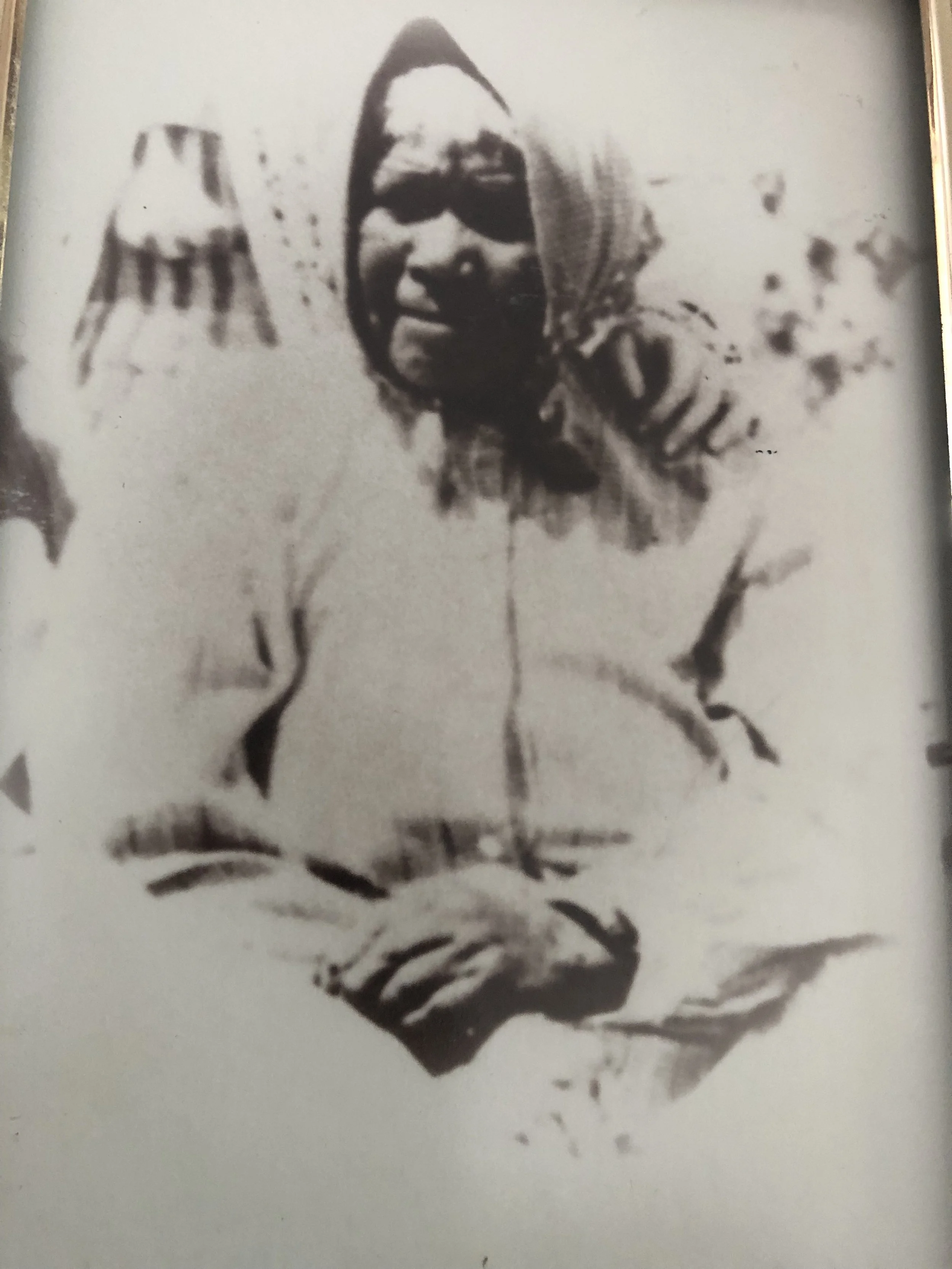

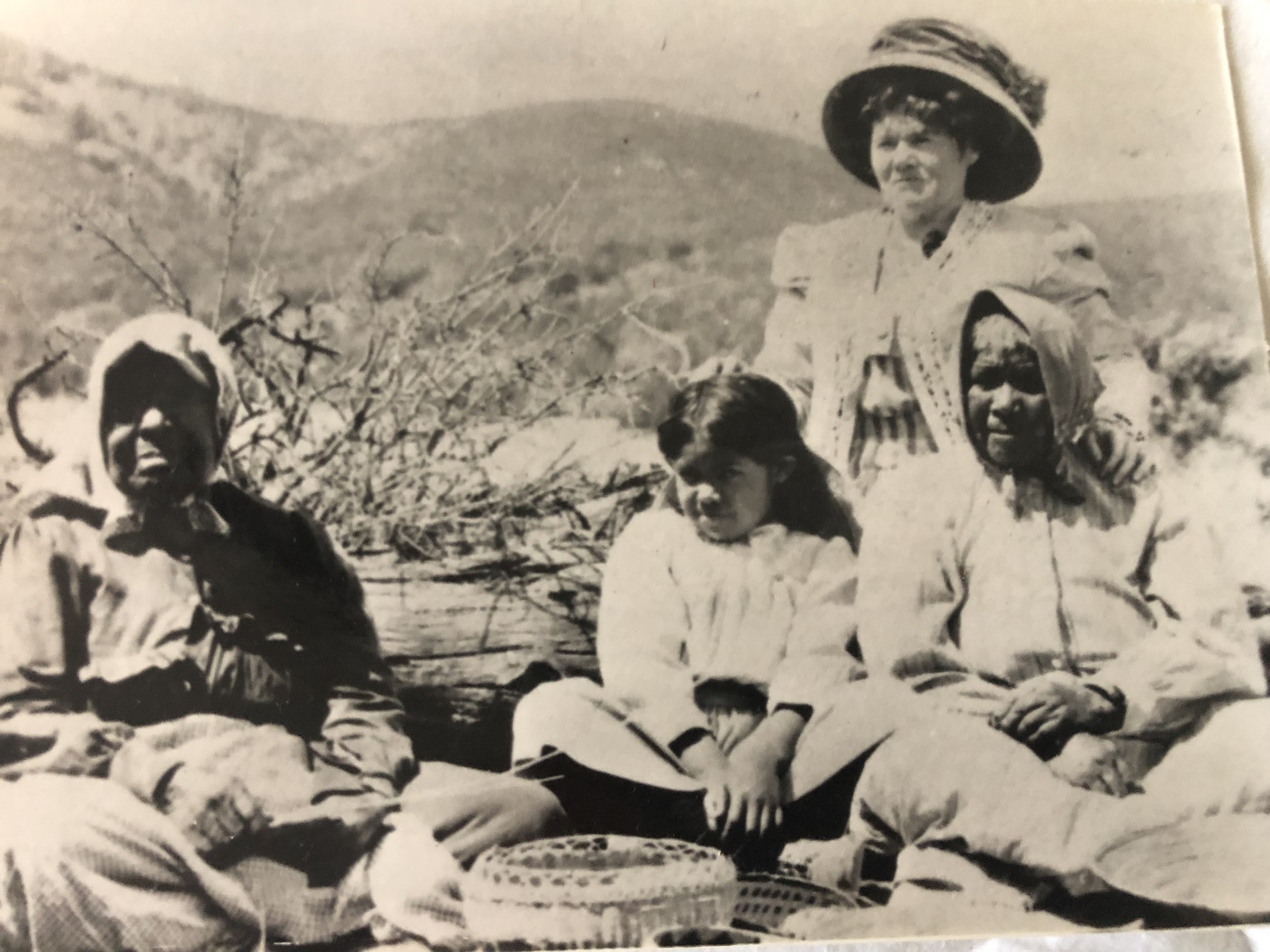

The handful of survivors intermarried with the remaing Indigenous peoples, especially the neighboring Hill Patwin (Walker 2016: 67-70). These descendants largely came to identify with the more dominant non-Pomoan communities. One line of descendants, however, intermarried with European-Americans in the early twentieth century. This line, all descends from “Mary,” a Chhé’ee Fókaa woman interviewed in by the Alfred Kroeber, a founding anthropologist at the University of California at Berkeley (Karen Moore and Theresa Moore, p.c.; Kroeber, Pitkin Papers).

Mary (whose Indigenous name is no longer known) married an American settler, Ben Moore, and soon gave birth to a son, Richard Moore. While her son was very young, she fled her husband to return to the Chhé’ee Fókaa homeland in the area of Stonyford, where she remained. This son would go on to marry a local white woman (an unprecedented act in early 20th-century California). Richard Moore’s son, Lawrence Moore (“Sharky” to his friends, family, and in the literature), would be raised in both the American and Pomoan worlds (Karen Moore and Theresa Moore, p.c.). Though not a fluent speaker, he would learn many important Chhé’ee Fókaa language words for Indigenous sites and the flora and fauna of the Stonyford area (Oswalt, SCOIL).

This line of Mary’s descendants was never part of a federally recognized tribe, but they were frequently visited by scholars seeking to understand the history and culture of the Indigenous community of the Stonyford Area. For example, Sharky was recorded by linguists, including Sally McLendon and Robert Oswalt (McLendon 1958; Oswalt SCOIL). Among Sharky’s grandchildren, Theresa Moore, Karen Moore, and Deb[ora] Ingham (SP) have been interviewed and recorded by the linguist Neil Alexander Walker, who published the first scholarly article devoted to the Chhé’ee Fókaa language (Walker 2016). Dr Walker is currently preparing a grammar and dictionary of the Chhé’ee Fókaa language, a project that was partially funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation in 2015-2016.

In an effort to preserve their language and sacred sites, including the remains of the ancient Chhé’ee Fókaa village of Bahkamtatri and burial grounds, the living descendants of Sharky Moore have come together as a community to create a nonprofit preparatory to beginning the long process of finally achieving federal recognition for their Tribe. Unless they succeed, one seventh of the Pomoan world is in danger of disappearing.

———-

Barrett, Samuel. 1904. The Pomo in the Sacramento Valley of California. American Anthropologist 6(1): 189-190.

Barrett, Samuel. 1908. The Ethno-Geography of the Pomo and Neighboring Indians. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. 6. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kroeber, Alfred. Unpublished field notes. Harvey Pitkin papers. American Philosophical Society.

McLendon, Sally and Robert L. Oswaalt. 1978. "Pomo." In Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8: California, ed. Robert F. Heizer, 274-288.

Oswalt, Robert. Unpublished field notes and audio recrodings for Northeastern Pomo. Survey of California and Other Indian Languages (SCOIL), California Language Archive. University of California at Berkeley.

Walker, Neil Alexander. 2016. "Assessing the Effects of Language Contact on Northeastern Pomo." In Language Contact and Change in the Americas: Studies in Honor of Marianne Mithun, ed. Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Diane M. Hintz, and Carmen Jany, 67-90. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

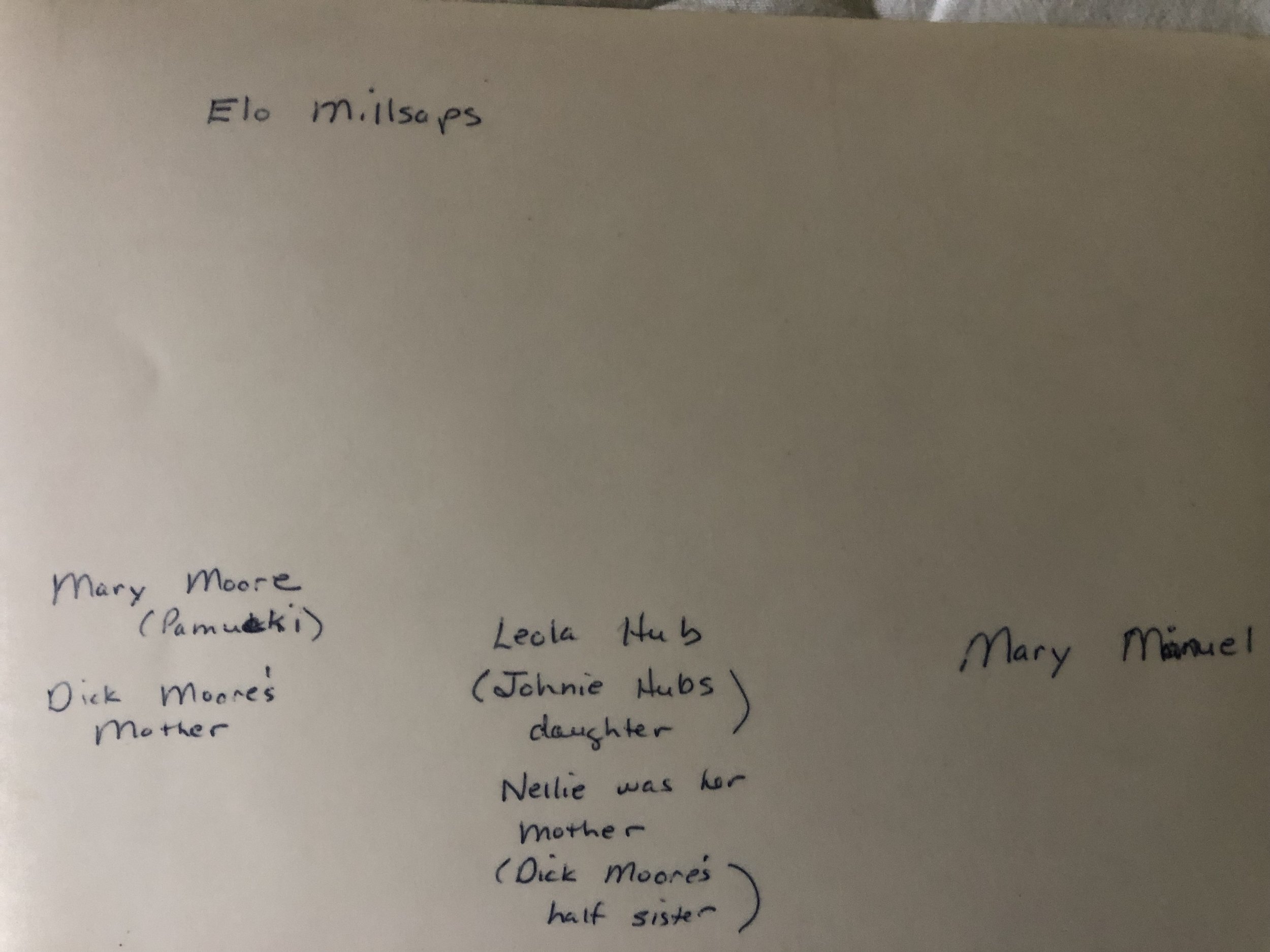

Mary Moore (née Pamucki), Dick Moore's Mother

Mary Moore (right), Mary Manuel (left), Leola Hub, Dick Moore's half sister (middle), Elo Millsaps (back)

Back of group photo